Life in Paris

Spring-Summer 1983

A history of the fashion press would emphasize those moments when journalists get lyrical, voicing their enthusiasms in memorable expressions that, sometimes, come to designate historic collections. It would highlight inflection points that gave rise to heated critical commentary. One such moment was the clothing revolution instigated by the Japanese designers upon their arrival in Paris in the early 1980s. The 1983 spring-summer collections of Rei Kawakubo (Comme des Garçons) and Yohji Yamamoto unsettled the fashion press. From what some called ‘rags that survived an atomic explosion’, a deliberate ‘poor look’ came to the fore. In a daily paper whose stock-in-trade is the description of haute couture evening wear, one could read this: ‘Raw talent (truly ‘raw’) in the service of clothes that disconcert, puzzle, irritate and disturb, because they are made for mutant women, not women like you or me. This is fashion from another world, namely the Japan that makes strict ‘miserabilism’ a new luxury. Forget that dresses, as a matter of course, have shoulders, seams, a waist, hips—here they have nothing of that, they ignore the tenets of Western clothes. But they influence all today’s fashion. Elegance has packed its bags. Even in Japan—or especially in Japan.’

Japanese designers created modernity with the help of holes and frayed edges. They banished the sacrosanct seam—rolled or appliquéd—taught in Western schools and ateliers,and left it unfinished. The unfinished, as difficult to master as the highly (excessively?) finished, is design. For the FW 1982-83 season, Yohji Yamamoto cultivated his provocations and limited them to cleverly ripped cottons out of which ample, gathered clothes were cut. Holes suddenly looked like ornaments. Is not lace made of filled and empty space? ‘After astonishment comes the time for reflection and seduction’: 1983 was the year of the Japanese. Yohji Yamamoto, who recognizes perfection in symmetry, is horrified by it and opts instead for ‘organized disequilibrium’. He now ranks among the creators of twentieth-century modernity.

Fall-Winter 1986-87

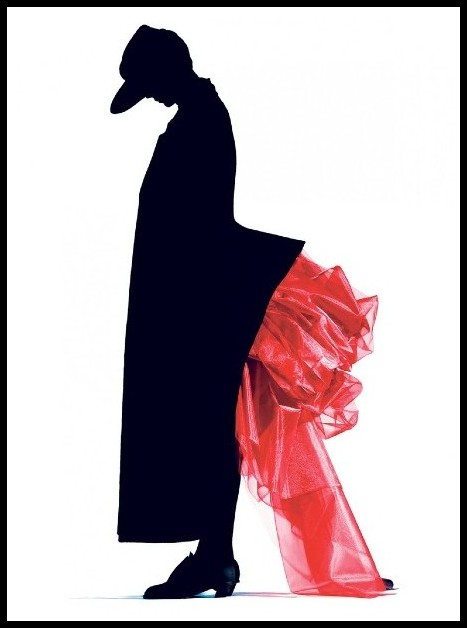

This collection, important in the creative itinerary of Yohji Yamamoto, is known first and foremost for its black coats with a red tulle bustle. Immortalized by the photographer Nick Knight (under the artistic direction of Marc Ascoli), the graphic coats also testify to the visual enterprise the Japanese designers inaugurated upon their arrival in Paris.

Invitation cards, collection catalogues, brochures—all abandoned official advertising formats in favour of a clearer statement of artistic intention. Spurred on by their example, fashion photographers now found it sufficient to convey the spirit of the clothing, even if that meant leaving out of the image the item of clothing itself.

Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo marked not only contemporary fashion but also the direction of photography. Their influence even extended to the boutiques, prompting a rethink of function and practice. The clothes, displayed in an interior characterized by clean lines, were more often laid flat than on hangers, and generated a synergy of form that magnified the impact of the display. If one sometimes hesitates to push open the door of these precursor gallery-boutiques, the clothing itself must not intimidate. Yohji Yamamoto, who has mastered the tailor’s art like no other, Rei Kawakubo, whose way with scissors needs no further praise, have gotten rid of the instruments of their scandal: the holes, the rags and tatters, the rips and tears. The FW 1986-87 show was an exercise in recomposition. Yamamoto ornamented trousers by folding flannel into handkerchief-style pocket flaps. He cut on the bias to create asymmetrical basques, white on black. On the heads of the models he placed hats with chin straps, on the hips ivory frock coats, jackets in toned-down acid-drop colours, and on the thighs skirts of chiffon and transparent tulle.

Overlong catwalks could do no damage to these horsewomen without horses. Like an ink drawing, a sketch embellished with red chalk, the black coats with red tulle bustle—one more example of Yamamoto’s technicity—moved through the hall with the fluidity and charm of a calligraphic line.